Why do writers write?

12 min

12 min

Why do writers write?

Why do writers write? 4 myths about being a writer

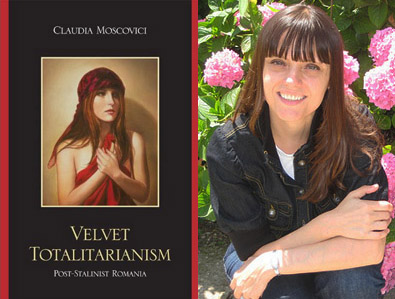

by Claudia Moscovici

In my career as a writer–of both fiction and literary/art criticism–I have encountered many myths about why writers write. Some of them I even believed myself when I was younger. It is tempting and glamorous to believe that writing is a profession that brings with it fame and fortune. In fact, the Romantic movement disseminated such a myth, presenting the writer as a free spirit that achieves greatness and immortality via his art or fiction. The reality of being a writer is, in most cases, very different and therefore so are the main motivations of contemporary authors. I’d like to describe some of those motivations by going over a few common misconceptions about writing.

Myth 1. Writing is a profession. It’s true that full-time writing takes as much time as any profession does. Moreover, writers seldom take breaks or vacations from writing. It is often an all-consuming enterprise. Ideas and inspiration don’t have a set schedule, even if the writer is very disciplined and writes regularly. Furthermore, a profession implies a more or less steady salary. However, few writers receive a steady income–enough to support themselves and their families–by writing. So, in that sense, writing is not a profession, at least not in the conventional sense of the term. It’s more of an all-consuming passion and a way of life in which the monetary rewards are uneven and uncertain. In the United States, where I live and publish, writers receive about 5 to 10 percent royalties from the profits made by their books. The percentage depends upon how many copies of their books are sold, how much they cost, and what kind of contract their literary agent (or they, themselves) have negotiated with the publisher. Generally speaking, the more books they sell the larger the author’s royalties, but it seldom exceeds 10 percent. Needless to say, unless your books sell as well as the Harry Potter or Twilight series—and sell movie rights on top of book sales—it’s difficult to imagine making a steady income for an entire family just by writing and publishing books.

Myth 2. Writers want to be famous. As they say here, good luck with that! As far as popular culture is concerned, you have much better chances of becoming famous if you’re an actor or pop star. We can take the Harry Potterseries as an example, since it’s so well known internationally. The principal actors of the films—Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint and Emma Watson—are far better known than the author of the series, J. K. Rowling, who is nonetheless one of the best known contemporary authors. Generally speaking, far more people would recognize in the street the actors as opposed to the authors of very successful books that have been made into movies. So if you want fame or external recognition, it’s best that you select a profession that is more visible in mainstream culture, such as singing or acting.

Myth 3. Writers want immortality. This is a very tempting Romantic thought for anyone who aspires to achieve greatness. But most professional writers are quickly disabused of this notion. “Immortality” is not a pure Romantic ideal; it’s more of a political and pragmatic reality. It depends upon the processes of cultural consecration. One of the best authors I have read on this subject is Pierre Bourdieu. His books, The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature and Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, explain all the politics and social hierarchies involved in making it into the canon, be it in art, music or literature. Attaining this kind of artistic “immortality”—which is so human and ephemeral after all—depends upon a very complex and heavily politicized process that does not favor most authors or lie within their (or their publisher’s) control.

Myth 4. It’s easy to publish. That depends on the avenue of publishing you try. Self-publishing is easy, since now anyone can print their e-books on Amazon Kindle. But the problem with that is that there are so many books out there that it’s tough to reach an audience. If you select this path, you won’t have the promotion or distribution budget that the major publishing houses have at their disposal. And if you want to publish with a large publishing house, at least in the U.S., then you have to go through the usually challenging process of finding a reputable literary agent who is able to place your book. A few years ago, I had the opportunity to have an inside peek at this process. When I was teaching at the University of Michigan, I organized a few panel discussions at the Ann Arbor Book Festival (in 2005, 2006 and 2007). In 2007, Amy Williams, who is Elizabeth Kostova’s literary agent, and Susan Golomb, Jonathan Franzen’s agent were two of the guest speakers in these panels. They discussed, among other things, the publishing process, explaining that they receive as many as 100 to 200 submissions a day from authors seeking representation. This deluge of queries is colloquially called “the slush pile”. Like most very successful agents, they usually sift through the queries and focus mostly on submissions by successful authors they know of or authors recommended by successful authors they know. Only rarely do they find in the slush pile unknown and unrecommended authors they wish to represent, and even in those cases, they are usually students at very reputable M.F.A. programs or have published with important magazines or literary reviews.

So if writing is not a great way to become famous, immortal or even earn a steady income, then why do so many of us want to become writers? I certainly can’t speak for everyone, but I can say that my main motivation for writing has been intellectual and artistic freedom. It’s something that many artists and writers prize dearly. There are few human endeavors as closely tied to freedom as writing. Here’s why.

a) First of all, a writer can’t really thrive without living in a country that respects and protects the freedom of speech. Granted, great writers emerged even during the worst totalitarian regimes. Maxim Gorky, the most prominent writer during the Stalinist era, is a prime example. But even he had to compromise his creativity and abide by the motto coined by Yury Olesha and paraphrased by Stalin himself: “The Production of souls is more important than the production of tanks. And therefore I raise my glass to you, writers, the engineers of the human soul” (Joseph Stalin, “Speech at home of Maxim Gorky,” 26 October 1932). This subordination of art and literature to ideology is one of the saddest thing a culture can do human creativity. It is an engineering of a state of soullessness rather than of the human soul. Writing and the freedom of expression are closely intertwined.

b) It is difficult to write as told. The creative process—particularly for writing fiction–is delicate, quirky and individual. Writers write not only in different genres, but also at different speeds; at their own pace. Some take a lifetime to write their masterpiece; others, like Balzac, write a novel a year. Some require daily discipline; others write in periodic spurts of inspiration. Nothing and nobody can dictate, from the outside, how writers should write. I know this is part of why I preferred being a writer to being an academic. Academic writing is constrained by area of specialization and technical jargon. Fiction is constrained by nothing. Only your capacities and imagination are the limit. “Everything you can imagine is real,” said Picasso. How true!

c) Your creativity is your only real guide. As a writer, you generally have to have in mind a target audience as well as what publishers can sell, to market your book. However, these are very abstract parameters. Nobody can really predict the public taste: not writers, not literary agents, not publishers. For publishers and literary agents, publishing success is like a very well informed gamble. Well informed because they study the market closely and have an intuitive understanding of what sells well. But nobody can predict the next best seller with a high degree of accuracy. That’s why literary agents represent between 100 and 200 authors and why the big, mainstream publishers in the U.S. publish about 200 to 300 books a year. Some of them are with established, brand name authors that are sure to sell well, but many of the new authors have only moderate success. Nobody could have predicted in advance, for instance, that a book of erotic fiction like Fifty Shades of Grey—a genre usually relegated to small, specialized erotica presses and that hasn’t been so wildly popular since Marquis de Sade made a splash in the eighteenth-century—would be this year’s best-seller. Go figure! For writers, agents and publishers alike, public taste is a wild card. You can aim to please a large mainstream audience, but your aim may or may not hit the target.

d) Writing is a celebration of freedom. This is a personal reason. It may not be applicable to all authors, but it was my main motivation for writing fiction. I left Romania as a child, while the country was still in the throes of the worst phase of Ceausescu’s repression. The communist regime had clamped down on the Iron Curtain, instituting increasingly stifling and repressive measures. I wrote my first novel, Velvet Totalitarianism, translated by Mihnea Gafita into Romanian as Intre Doua Lumi (Curtea Veche Publishing, 2011), in order to record palpably, through fiction, a very challenging historical period in Romanian history. I hoped that those of us who lived through it would remember it and that the new generations would learn about it. It’s important to keep in mind the communist past because it’s so easy to repeat it. Not necessarily in the same way, but through supporting similar forms of political repression or corruption that risk depriving us of the basic human rights and freedoms that make not only writing, but also living possible.

English

English

Français

Français

Deutsch

Deutsch

Italiano

Italiano

Español

Español

Contribute

Contribute

You can support your favorite writers

You can support your favorite writers